http://sungmoonchung.com/projects

The melting pot is behind us, that metaphor for a culture that many of us grew up in, a culture that diminished minorities and ethnic cultures, encouraging them to dissolve into the vast sea of the American Dream.

But does the culture of diversity that has replaced it simply re-stratify power; a slight of hand that is still built on the status quo? And who and what are driving this narrative, one that is largely defined by the tone of one’s skin or the way in which gender is equated with individual power?

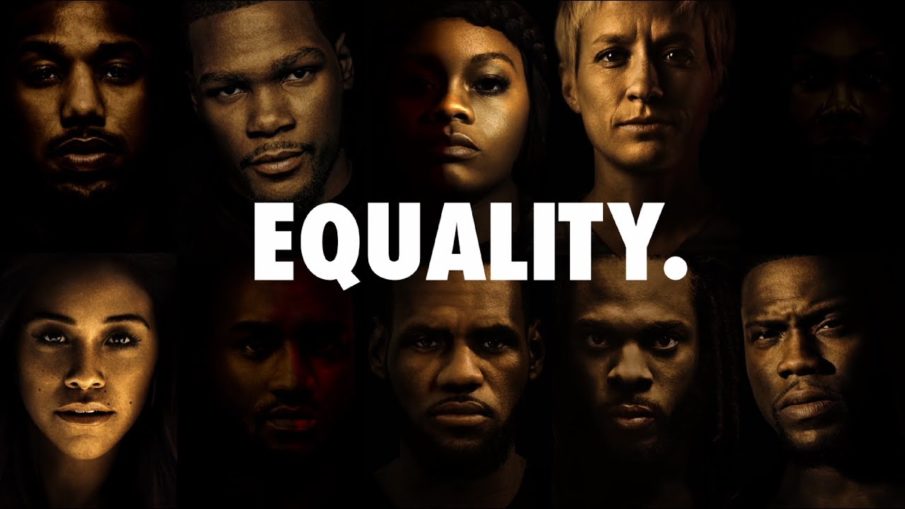

Corporate academia has sculpted this superficial vision, one that has been tacitly managed as a marketing tool rather than a reflection of genuine cultural sovereignty. Universities have invested heavily in departments of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. Colleges promote diversity in shiny pamphlets and websites, and photographs of student life display images of multiculturalism by exploiting images of minorities in advertising campaigns.

But what is this brand of diversity but a processing and distillation of remarkable human differences into commercialized stereotypes of the human form. The creation of a product that we have been conditioned to want; to consume.

And what is it that we are buying into? Sometimes, self-reflection brings us to a point of knowing, a look into the plurality of our own being, a chance to resist and reconcile the distorted imagery that is pushed upon us. I remember my own childhood that way, a point of departure for the rest of my life. We were poor, surviving under the poverty line, but my parents knew that the world was not a reflection of our own microcosm.

And I learned then that the experience of true diversity is a venture into the unknown, a mingling of vastly different worlds, and that sometimes, this experience is raw and unrefined.

My own children are hybrids. They are inventions of their own design, products of two wildly different cultures and ethnicities, an intricate and ancient lineage, one that cannot be contained.

But we are bandwagon consumers, trained to conform, to buy shiny and stylistic things; meaningless products that appeal to the status quo. A status quo that was constructed by and for the upper classes, the suburbanites, the elites, those comfortably situated who imagine that they can purchase anything, even the illusion of a diversity that has been packaged and predefined.

The rhetoric of diversity sounds from the most malignant features of corporate structures and bureaucratic capitalism, systems that many so fashionably claim to reject. Now those naysayers buy into a new cultural tokenism, one built on cannibalized images of human heritage that are fashioned into products and selling points.

And in this new vision, who really cares about the intricacy of culture, the rich and sometimes uncomfortable acknowledgement of traditional differences? Who wants to mingle with the downtrodden, the poor, the swathes of still marginalized victims of a system that sells them out time and again?

Workers at various factories for name brands in India, who live mostly in poverty, allowed the BBC to photograph them anonymously

And where is inclusivity for the countless brown and black faces, the gritty and invisible who are on the other side of this divide? Those who toil endlessly in factories, earning a pittance, to create all the accoutrements for lifestyles we strive to maintain?

In the end, there can be no authentic recognition of diversity, no equalitarianism in this world of human commodification, or a world in which the lesser valued are kicked aside, no matter their color or race. A world in which one’s value is determined by class or social status.

And won’t we always be fractured until we look beyond the institutional rhetoric that confines us, the systems that define and minimize, toward the interiority and authenticity of our own design.

Workers at various factories for name brands in India, who live mostly in poverty, allowed the BBC to photograph them anonymously

Heffernan Research offers a range of English language tutoring options. Individual and small group sessions are available. Special classes on focused topics, such as essay writing, are also offered throughout the year. Margot works with ESL students as well as individuals who need to enhance specific English language skills.

Heffernan Research offers a range of English language tutoring options. Individual and small group sessions are available. Special classes on focused topics, such as essay writing, are also offered throughout the year. Margot works with ESL students as well as individuals who need to enhance specific English language skills.

Margot Heffernan has solid and extensive experience writing about a broad range of medical topics. She uses her expertise to provide comprehensive and academically sound papers for medical malpractice, product liability, and personal injury lawyers as well as other professionals who need reliable medical information.

Margot Heffernan has solid and extensive experience writing about a broad range of medical topics. She uses her expertise to provide comprehensive and academically sound papers for medical malpractice, product liability, and personal injury lawyers as well as other professionals who need reliable medical information.